On a chilly October day in 2015, 24-year-old Rami Anis boarded a rubber boat in the Aegean Sea in Turkey. His destination was Europe and his goal was a better life away from war and hardship.

Looking at the people around him on the boat, he was horrified. They were children, men, and women. The fact that they might not make it never escaped his mind, even though he is a professional swimmer.

“Because with the sea, you can’t joke,” said the Syrian refugee.

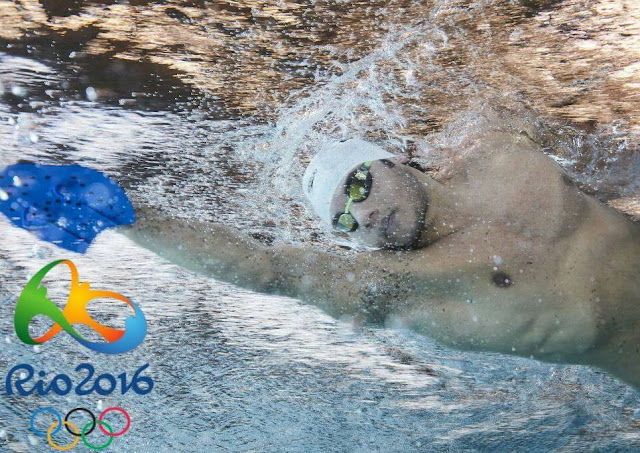

But on Aug. 11, Rami will not be worried about swimming in the sea. He, instead, will be swimming at the Olympics. He made it safely to Belgium after days of heart-wrenching journey, from Istanbul to Izmir to Greece before setting off a trek through Macedonia, Serbia, Croatia, Hungary, Austria, Germany and eventually Belgium.

Rami will be competing at the 2016 Olympic Games in Rio de Janeiro as a member of the Refugee Olympic Team — the first of its kind — and march with the Olympic flag immediately before host nation Brazil at the opening ceremony.

Rami’s determination to achieve his sporting dreams led him to accept life’s challenges and never quit. He was not a quitter, even when life struck so hard on him and his family.

When war broke out in his hometown of Aleppo, he fled to Turkey. He had originally thought that he would only stay for two or three months at the most and then go back to his country.

Little did he know, like many of his fellow Syrians, that it had become much more complicated. Life was uncertain and his athletic future was hanging in the air.

“We couldn’t think forward because the longer the war was taking, the less we knew what the future was hiding,” Rami told me over a voice call on Facebook messenger.

But he continued training for four years in Turkey. He paid for the training from his and his brother Iyad’s own money. However, as years passed, achieving his dream to represent a professional team faded, even though he trained at the prominent Galatasaray Sports Club. As he did not have Turkish citizenship, he was unable to swim competitively.

“I was very patient for four years without any support or participation. I had lost hope. The war seems never-ending and even if it did, how would I go back? No swimming pools are left. Nothing is left,” he said.

And so, he decided to be smuggled to Europe. There were no opportunities in Turkey to advance his sporting life. As soon as he arrived Belgium and resettled there as a refugee, Rami was connected with Carine Verbauwen, a former Olympic swimming finalist who later became a coach. Rami has been training at her club, S&R Rozebroeken in Ghent, Belgium.

These baby steps in Belgium put him back on track until a greater opportunity opened up. Last January, IOC head Thomas Bach visited the Eleonas camp for refugees and migrants in Athens. There, he announced that top athletes who are refugees with no home country to represent will be allowed to compete at the Rio Games under the Olympic flag.

Rami contacted the IOC immediately and boom, it was a matter of selection. Last June, he was selected among 10 refugee athletes. They include two Syrian swimmers, two judokas from the Democratic Republic of the Congo, a marathoner from Ethiopia and five middle-distance runners from South Sudan.

Even though Rami is competing under the IOC flag and not his country’s, he still hopes to represent his beloved Syria someday.

“There is nothing more invaluable than one’s homeland,” he said.

This post was originally published on the World Bank Voices blog.